Pollen

|

|

|

|---|

|

Pollen |

Willow as a diverse habitat benefiting pollinating insects in early spring |

|---|

A thesis submitted to the University of Glamorgan By

SYLVIA M. BRIERCLIFFE

In candidature for Higher National Certificate in Environmental Management

May 2005

Chapter 1 - Introduction

1.1 Aims

The aim of this project will be to research aspects of the success of native Willows as a diverse habitat benefiting hundreds of species of organisms, from all Kingdoms of life, and will deal specifically with the beneficial influence of early pollen produced by male catkins on the feeding habits of social insects.

The study has centred on three of the factors, which contribute to the habitats' diversity. Using literature from the 17th to the 21st century, it will examine some of the discoveries that botanist and ecologist writers have made to understand ecosystems in Britain and abroad. These three contributory factors are

1. Willow species,

2. Flower production,

3. Hymenoptera species of insects.

1.2The objective

The objective will be to examine the importance of willow as it was recognised in the past by contemporaries of Samuel Pepys and in the present day to writers on conservation and ecology for it's value in conservation of wild life.

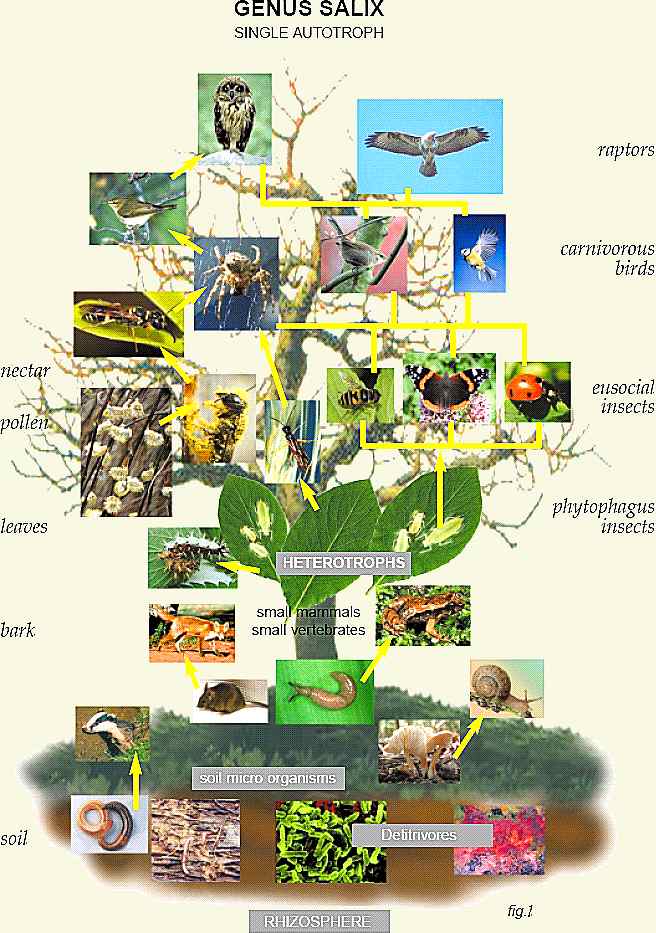

Fig.1 - Typical Food Web associated with Salix Species (Courtesy Diana Broadbent )

1.3 Willow - Family Saliciceae - Genus 'Salix'

History contains many references to the value of trees to mankind, as fuel, building material, animal fodder, shelter and tools.

As early as 1664 John Evelyn (1664) was commissioned by King Charles II to study the loss of the Royal forests and advise methods for regenerating and replanting them. Timber was an economic necessity, to provide a building material for boat construction, and for houses, churches, and tools.

Culpepper (1826) in his book 'Complete herbal & English Physician' writes about Willow Tree herbal cures, many precursors of medicines used today.

In 'Flowering Plants of the World ' (Ed Heywood V.H.1978) it is stated that there are 350 Salix species world wide; distributed mainly in the North Temperate zone, but world wide except Australasia The description of willow species mentions 'one or two knob like glands at the base of each flower. These glands secrete sweetly scented nectar and are very attractive to moths and bees, a very important source of food for bees'.

Newsholme (1992) in a comprehensive study of willows discusses the origins and history and details 333 species and many varieties. He is interested in their ornamental value, botanical characteristics and variety.

German scientist Haeckel (1869) introduced the term Ecology (" the study of animals and plants in relation to their habitats" His studies and those of 20th century writers Elton (1927) and others, added to the knowledge of ecosystems and recognition of the value of willow as a habitat. The development of more powerful microscopes has led to a more complete understanding of the contribution of microorganisms and primitive fungi and bacteria to the existence of Food chains and Food Webs.

Environmental studies are highlighting the value of Britain's Indigenous trees, including native willows to the preservation and conservation of all wild life. The significance of native species is recognised, and the aim is to conserve habitats for hundreds of species of organisms, maintaining the rich diversity of nature.

Emberline (1983) writing about ecosystems describes a typical biotic component.

Of :

a) Producers, autotrophs

b) Consumers, heterotrophs

c) Decomposers. Detritivores

A single autotroph (willow tree) supports thousands of organisms and hundreds of different species, and a pyramid of numbers can give an idea of the numbers of organisms supported by a single autotroph.

Ailner (1992) quotes Southwood's studies, stating that there are 450 phytophagus insects associated with indigenous willows. This study is specifically interested in the value of willow to pollinating insects, in particular Apis mellifera, (the honey bee) an insect belonging to the Hymenoptera Order. These insects are not damaging to the willow leaves or flowers and are therefore not included in the 450 mentioned by Southwood.

1.4 The Flowering of willow:

The botanical characteristics are of special interest in this study Newsholme (1992) states that all willows are dioecious, all male catkins being produced on one plant. They start to flower very early, S. caprea, goat willow as early as January, other species are in flower until April providing a constant supply of pollen and nectar. This is significant in the production of pollen when few flowers are available to insects.

The flowers are inflorescences, taking the form of catkins, which develop in a familiar way, through the loss of the bud scale and the revelation of the silky hairs of the 'Pussy Willow'. Eventually, however, the anthers surmount the filaments of the stamens and reveal a vivid display of pollen from pale yellow through gold to shades of red and purple depending on the species. Both male and female flowers bear nectaries, often two and often exuding scented nectar.

The identification of the different species and varieties of Willow is difficult. There are many hybrids, sometimes of three species. (Newsholme, C 1992)

1.5 Hymenoptera- Insects, Bees, wasps,

The life history and reproductive cycle of the honeybee will be explained and the significance of pollen as a food to this and other species of eusocial insects.

Metamorphosis of Apis mellifera, through egg to adult requires careful feeding by the workers in the colony. The larval stage requires a source of nitrogen rich protein, which workers bring into the colony as pollen. Later in it's development the growing bee requires carbohydrate in the form of nectar, which the workers also gather.

Entwistle (1976) states that 'There are at least a million known species of insects' which are classified in the phylum Arthropoda.

McGavin George, C (2003) traces insect's origins in fossil records as long as 543 - 510 million years ago.

The Hymenoptera (insects) evolved capable of flight and together with the Angiosperm Class of flowering plants.

Strong, Lawton and Southwood (1984) have written extensively on the effects of insects on flowering plants, but their interests are primarily the phytophagus insects feeding on tissues of living plants. They write about insects that feed externally, by biting, chewing, or mining into their host, or suck from the cells, these are indeed the 'pests' of horticulture, but also a part of the food web for other organisms. Their contribution to the food web is essential.

The Hymenoptera, on the other hand are vital pollinators, benefiting both plants and insects. They feed only on the pollen and nectar, which they transport to their colonies. They are known as social /eusocial insects.

1.6 The Hypothesis that:

'Early in the year insects benefit from pollen of various willow species'

will be tested by experiment and by Literature Review. (And by personal communication with Beekeepers, and

Countryside rangers.)

Chapter 2 - Literature review

This study is concerned with the symbiotic relationship of willow with visiting insects particularly in the early spring and the value of pollination 'in exchange' for quantities of nectar and pollen.

Using literature from the 17th to the 21st century, it will examine some of the discoveries that botanist and ecologist writers have made to understand ecosystems in Britain and abroad. The three contributory factors to ecological benefit are

1. The Willow species,

2. Botanical characteristics of flower production,

3. Hymenoptera species of insects.

2.1 - The Willow - species

2.1.i - Historical Evidence

Evelyn J (1664) studied 24 species of British trees, which included Salix varieties. These were grown for their quick regeneration after being coppiced or pollarded. He advised on their propagation, regeneration by pollarding, and coppicing and the maintenance of a continued supply of willow stakes, because of their use for tool handles, fences, vine supports and baskets. In his book 'Sylva' (Chapter 21: 8) He states that "If some be permitted to wear their tops five or six years, their Palms will be very ample, and yield the first, and most plentiful relief to Bees, even before our Abricots blossom".

In the nineteenth century Culpepper (1826) the famous herbalist in his book 'Complete herbal & English Physician' writes about Willow Tree herbal cures, many of them precursors of medicines used today.

There was no recording and recognition of Willow trees for its value to wildlife. Evelyn and Culpepper were writing about willow, but it was for the tree's value to man, although both these writers appear to derive a spiritual element to their love of willows.

The Family Salicaceae - Populus, and Salix genus, is a taxonomically isolated family consisting of 4 Genera. But there appears to be confusion about the origins of Salix. Newsholme ( 1992) states that some botanical evidence supports findings that a small genus Chosenia has basic Salix characteristics; and some members of the Genus Populus - of pre Salix origin - are now included within the Genus Salix-- under the name Urbanianae They may have originated from within the sub-tropics . However Heywood and Mitchell do not mention these similarities and differences. They recognised only Populus and Salix which are undoubtedly more familiar.

Fig 2.1 Distribution of Salicaceae species showing widespread varieties except in Australasia.

Newsholme C ( 1992) in a comprehensive study of willows discusses the origins and history, and details that there are 333 species and many varieties.

He is interested in their ornamental value, botanical characteristics and variety.

Heywood (1978) describes the probable origins and the global distribution of The Salicaceae family. Salix was among the earliest recorded pre-Ice Age flowering plants to colonise the glacial sediments spreading for considerable distances across Europe, Asia, and North America. In 'Flowering Plants of the World' he states that there are 350 Salix species world wide; distributed mainly in the North Temperate Zone, but world wide except Australasia. His description of willow species mentions 'one or two knob like glands at the base of each flower. These glands secrete sweetly scented nectar and are very attractive to moths and bees, a very important source of food for bees'.

There are two main genus in this family, common to the British Isles and Europe. i.e. Willows and Poplars. There are 19 Willow species native to Britain. (Mitchell, A., 1978)

2.1. ii - Botanical

Botanically willows are usually small trees or shrubs (however S. alba, S fragilis and S. caprea grow to more than 15m in fertile soil). They are dioecious bearing 2 female or male flowers on different plants. (One: S aegyptiaca, very rare exception has male and female flowers and is particularly sweet scented)

Many garden willows will have been propagated vegetatively by plant breeders and will only be known as one sex. E.g. S. sachalinensis 'Sekka' which is a male clone, and often displays the phenomenon of fasciation.

However the S. x chrysocoma (syn. S. vitellina pendula) the familiar large Weeping Willow in many parks,'has both sexes on the same separate branches, or is androgynous, bisexual or with female flowers at the apex of the catkin.' according to Newsholme (1992)

Willow is zoophilous - insect pollinated, but the seeds are wind dispersed.

Native Willows

| S. pentandra | native to North Wales and northern England | |

| S. fragilis | Crack Willow | |

| S. alba | White Willow | |

| S. caprea | Goat willow | |

| S. cinerea | Grey willow | |

| S. repens | Creeping willow | |

| S. viminalis | Common osier | |

| S. herbacea | [Snow bed willow (Canadian name)] |

Figure 2.2 - Weeping Willow - S. chrysocoma

There are also many hybrids, the origin of which botanists are still debating among themselves.

They are familiar trees in the Northern Hemisphere, being tolerant of soil and climate. There are however, few varieties that flourish on limestone or chalky soils although willows will tolerate a large range of pH values growing successfully between pH 5.5 - 7.5. They do not need a fertile soil and flourish in a variety of climates. S. alba is a common tree in damp watermeadows, but S. repens colonises sand dunes. Hybrids based on S. viminalis are pioneer species on cold, wet, sites at high altitudes, or on the coast. Ailner J.E. (1992) adds that willow distribution spreads northwards into the Arctic Circle further than any other tree.

The properties of Willow that contribute to its value as a habitat are the ease with which it grows.

It survives in most localities in soil of pH 6.0 - 8.0 Most soil types Most topography

There are species of Willow, which are adapted to different conditions:

S. alba - low lying conditions

S. fragilis - river bank

S. herbacea - mountains Scotland.

S. repens - colonises sand dunes.

2.1. iii The ecological importance

German scientist Haeckel (1869) introduced the term Ecology ("the study of animals and plants in relation to their habitats") His studies and those of 20th century writers Elton (1927) and others, added to the knowledge of ecosystems and recognition of the value of willow as a habitat. The development of more powerful microscopes has led to a more complete understanding of the contribution of micro organisms and primitive fungi and bacteria to the existence of Food chains and Food Webs.

Ailner also in 'The Tree Book' tells us that Kennedy and Southwood list 450 phytophagus invertebrates associated with Salix, - more than any other tree. These include 162 different butterflies, 104 different species of bees and wasps. A number of fungi are specifically associated with willow. Often willows have more than one nectary, exuding sweet scented nectar which makes them very attractive to wasps, bees and moths who gather the pollen and nectar which is produced very early in Spring when it is most needed for the brood of these insects, of specific interest to this study.

Native Salix species are usually shrubs or small trees, they are not ecologically dominant and do not form forests. However they are pioneer species, often colonising scrubland. They are found growing among industrial buildings and railway sidings. They are abundant in hedgerows providing wild life with 'corridors' in which to migrate.

There are species suited to low-lying conditions and also species growing up mountains.

Their value as a habitat is perhaps greater than any other common tree.

Newsholme, C (1978) mentions many birds, willow warblers, wagtails, wrens, and the tit family. These are all insectivorous, and the open crowns following the pollarding of willows are ideal nesting places.

However there has been little recording and recognition of Willow trees for their contributions to ecology, and as habitats for a rich diversity of native species of fauna and flora. Oak Trees appear most often in literature, as examples of a diverse habitat.

When Ailner (1992) quotes Southwood who states that there are 450 *phytophagus insects associated with indigenous willows, he is studying herbivores, who either eat parts of the plant themselves, or whose larva feed of it. This study is concerned with the value of willow to pollinating insects, in particular Apis mellifera.( the honey bee) an insect belonging to the Hymenoptera Order. These are not damaging to the willow leaves or flowers and are not included in the 450 mentioned by Southwood; but provide a pollinating service to the tree.

The willow species are the basis of a vital food web for insects, birds, small mammals, larger animals; many soil organisms, bacteria and fungi. They are a very important habitat.

Ecological Pyramids and Energy Flow Food chains are useful for ascertaining the flow of food in an ecosystem, but give no indication of the number of organisms involved at each level. All indigenous trees provide a diverse habitat, but many botanists agree that willow is among the richest.

A reverse pyramid representing Energy Flow shows the ratio between producers and consumers associated with an Oak Tree.

The Energy Pyramid of Number for willow (figure 2.3). This resembles the Energy Pyramid for the Oak, which is represented in (figure 2.4).

Figure 2.3 - Pyramid of Numbers involving a Willow Tree

Fig 2.4 - Pyramid of Number involving Oak tree

(Chigwell -school (2004) Web Site www.chigwell-school.org) [re-drawn to same scale as fig 2.3]

However a vital part played by detritivores should be acknowledged in both diagrams, but Fig 2.4 illustration does not take into account the value to Energy flow of the detritivores in an ecosystem.

Environmental studies are highlighting the value of Britain's Indigenous trees, including native willows to the preservation and conservation of all wild life. The significance of native species is recognised, and the aim is to conserve habitats for hundreds of species of organisms, maintaining the rich diversity of nature. A single autotroph (willow tree) is supporting hundreds and thousands of different organisms and species.

In Europe and the U K, a new willow habitat is being created by short rotation coppicing (SRC); which is an initiative for biomass as potential fuel production, as an alternative to the use of fossil fuel. In an interesting project in Denmark Redderson, J. (2000) researched 'SRC Willow (Salix viminalis) as a resource for flower visiting insects.' .He says 'sex composition in the dioecious willows has profound implications for flower-visiting insects: female flowers produce only nectar while male flowers produce both nectar and pollen.' While nectar is important as an easily digestible energy source, pollen is an important nutritious food resource for reproduction colony growth for honey bees, bumble bees and insects in early spring.

It is an exciting possibility that biomass fuel production using suitable varieties of willow may have a beneficial effect, by providing a rich habitat where nothing existed before.

Another biological pollution solution being investigated by Nottingham University is the phytoextraction of sewage sludge using SRC willow to remove heavy metal contamination.

2.2 - The botanical characteristics and flower production

These are of special interest in this study. Newsholme (1978) states that all willows are dioecious, all male catkins being produced on one plant. They start to flower very early, S. caprea, goat willow as early as January, other species are in flower until April providing a constant supply of pollen and nectar. This is significant in the production of pollen and nectar when few flowers are available to insects.

The flowers are inflorescences, taking the form of catkins, which develop in a familiar way, through the loss of the bud scale and the revelation of the silky hairs of the 'Pussy Willow'. Eventually, however, the anthers surmount the filaments of the stamens and reveal a vivid display of pollen from pale yellow through gold to shades of red and purple depending on the species.

As Begon, M. Harper, J.L. & Townsend, C.R.(1986) state that production of nectar seems to have no value to a plant except to attract animals.

Both male and female willow flowers bear nectaries, often two and often exuding scented nectar. This is important in the mutual benefits between willow and the insects, which visit, or live in the tree.

The identification of the different species and varieties of Willow is difficult. There are many hybrids, sometimes of three species. Newsholme, C (1992)

The Table below illustrates the various flowering times of the different species of Willow; which improves the availability of pollen and nectar over an extended period in spring.

Fig 2:5 Table of flowering (Science and Plants for Schools) Web Site

| Species | Common name | Flowering month | Length of catkins |

| S. caprea | Goat willow | 3 / 4 | 2-3 cms |

| S. cinerea | Grey/ Fen willow | 3 / 4 | 2-3 cms |

| S. fragilis | Crack willow | 4 / 5 | 4-6 cms |

| S. alba | White willow | 4 / 5 | 3-5 cms |

| S. purpurea | Purple Willow | 3 / 4 | 1.5-3 cms |

| S. pentandra | Bay Willow | 2-6 cms |

2. 2.i Nectar and Pollen

Nectar is brought into the hive (or cells in the case of wild bees) with water, and this is the main source of carbohydrate for the energy needs of the colony. Willow flowers are a rich source of nectar, both male and female flowers having at least one and some varieties more than one nectary.

Newsholme (1992)

Pollen is a product of the male flower, a ' microspore of seed plants' (Penguin Dictionary of Botany 1984) In insect pollination, pollen is often barbed or sticky, in wind pollination it is smooth and light.

The pollen grain has two protective walls the intine and the exine. The outer exine is provided with pores that are not actually openings, but the wall is very thin. (This thinning of the wall allows the pollen tube to grow out.)

The grains also change shape as water is absorbed. The surface may have a characteristic shape and the pores intricately and delicately sculptured. The exine will often take up the colour of a staining agent and in this way palynologists can identify the plant genus. Additionally the pollen grains vary considerably in size, for example Myosotis -forget-me-not : 7µm Zea - Maize 85 µm

(See Appendix 1 for microscope images)

Fig 2.6 Pollen Calendar produced by N.P.A.R.U.

This pollen calendar is produced to inform Hay fever patients about the likely times of the year they may be affected by various pollens. Most of these pollens are wind blown and of no value to pollinating insects.

2.3. Hymenoptera- Insects, Bees, Wasps.

2.3. i Insects

The Binominal System classifies organisms into Kingdoms- Orders -Families

The Animalia kingdom contains The Insecta, which contains the Order Hymenoptera of which Apis mellifera is a member.

Rowland Entwistle, T (1976) states the "There are at least a million known species of insects." His estimate covers the other 28 orders besides Hymenoptera.

McGavin G. C. (2001) in the Introduction to his book 'Essential Entomology' states that "Terrestrial and fresh water food chains are dominated by insects at every tropic level above that of plants" and that insects pollinate the vast majority of the world's 250.000 or so flowering plants. He states, "Using insects as 'flying genitalia' is a marked improvement on wind pollination."

The Hymenoptera (insects) evolved capable of flight and together with the Angiosperm Class of flowering plants, and scientists trace their origins in fossil records as 543 - 510 million years ago.

Zahradnik J. (1991) investigated estimates for the total number of species of Hymenoptera in Europe; he suggests 350,000 species of bees, wasps and allied insects. Their common feature gives them their scientific name from the Greek hymen (membrane) and pteron (wing).

Whole groups of the species care for their offspring, wasps by providing parasitised insects for the larva to eat. In one case, the European Bee Wolf (Philanthus triangulum) feeds her grubs on parasitised honey bees, (fortunately this predator is not common in U.K.)

Southwood T.R.E. has written extensively on the effects of insects on flowering plants, but his interests are primarily the phytophagus insects feeding on tissues of living plants. He writes with other entomologists, Strong and Lawton, (1984) about insects that feed externally, by biting, chewing, or mining into their host, or suck from the cells, these are indeed the 'pests' of horticulture, but also a part of the food chain for other organisms.

Fig 2.7.. The community of phytophages found on S. caprea

(Strong. D.R., Lawton, J.H., Southwood, T.R.E., 1984)

2.3. ii The eusocial insects

The Hymenoptera, on the other hand are vital pollinators, benefiting both plants and insects. They feed only on the pollen and nectar, which they transport to their colonies. They are known as social /eusocial insects.

The life history and reproductive cycle of the honeybee will be explained and the significance of pollen as a food to this and other species of eusocial insects.

Zahradnik, J. ( 1998 ) tells us that like many other higher insect orders (Coleoptera, Diptera and Lepidoptera) the Hymenoptera undergo complete metamorphosis, as shown in Fig 2.8

Figure2.8 - Life History of the Apis Mellifera

2: 3.iii Bees- specifically honey bees ( Apis mellifera )

In this study the writer has centred information on the honeybee, although other social species of bees and wasps have similar methods of brood rearing.

Metamorphosis of Apis mellifera, through egg to adult requires careful feeding by the workers in the colony. The needs of the colony are for

Pollen, Nectar, Propolis and Water.

The pollen provides protein, for the growth of the larva, the nectar provides carbohydrate for all the energy needs of the colony and the water is needed for all the metabolic processes.

The reproduction of insects is somewhat complicated, including that of the honey bee.

The eggs of the honey bee are parthenogenetic, (Hooper T 1979) those which have been fertilised, produce females; and those unfertilised, produce drones. The eggs laid by the Queen are laid in three kinds of cells, according to what caste of bee is required by the colony. The difference in caste produced lies also in the feeding of the egg and larva.

The larval stage requires a source of nitrogen rich protein, which workers bring into the colony as pollen. Later in it's development the growing bee requires energy from carbohydrates in the form of nectar, which the workers also gather. Hodges, D. (1984) in her book "The Pollen Loads of the honey bee" states that adequate supplies of pollen are required in the hive at all times and a source of pollen is crucial in the autumn for the survival of the colony over winter. Flowering ivy is a good source of pollen at this season.

She describes in her book the pollen packing process; of bees on poppies (papaver) - these flowers yield only pollen. The bee scrambling among the anthers gets dusted all over with pollen grains. She leaves the flower and hovers, stroking her tongue over her forelegs and moistening the pollen with regurgitated honey. Using brushes on her legs and the antennae on her head.

In a series of actions she moulds the pollen pack around a single hair on her corbicula (pollen basket) Bees will usually collect from only one species of flower in one foraging trip. Some bee species are monolectic; they totally depend on the pollen and nectar of one species of flower.

The larva in the brood, which is building up at the beginning of the year are fed on 'Bee Milk' in large amounts for the first three days, and then in small quantities until the cell is capped on the eighth day. It is the mixture of nectar and pollen, which is provided by the willow species at this important time; and from which is produced, the bee milk. The 'nurse bees' whose sole existence is to rear the worker larva (and if the hive requires it, produce a new queen, by modifying the feeding schedule.)

Fig 2.9 Bee packing Salix pollen.

Pollen grains that have been stored in the hive will lose their vitamin content. Fresh pollen contains pheromones, which stimulates the queen to commence laying.

Hodges also tells us that the willow pollen grain is 18 µm. Factors which may aid identification of pollen are: the size and colour of grains, the knowledge of local flora and the flowering dates.

The British Beekeeping Association Website Dennis, B,P (2005) www.bbka.org.uk/ in their management articles state that brood rearing is initiated by increasing day length; but colonies do not start to build up until temperatures increase to 10°C+

The life of the honey bee has been manipulated by humans to the advantage of both. Originally hived in straw skeps, the beekeeper now cares for his bees in a wooden hive designed to enable excess honey to be retrieved without disturbing the brood chamber or the clustering bees. He can make sure they have sufficient food and protect them from extremes of weather. Hooper, T (1979 ) in his introduction to 'Guide to Bees and Honey' says 'many people get carried on a tide of interest into a relationship with this marvellous insect which is so unlike ourselves and yet lives in cities of 60,000 strong, without our need for councils'.

Fig2. 10 Foraging honey bee, BBKA photograph

Chapter 3 Methodology

1.1 The Experiments

The Hypothesis to be tested was that:

'Early in the year insects benefit from pollen of various willow species'

The National Pollen and Aerobiological Unit produce a Pollen Calendar which gives the timing of pollen production by allergenic plants.

It is true that it is mainly the wind-pollinated species, which cause trouble to allergy sufferers with the very small, light pollen that they produce. It is interesting to compare the early flowering and the length of flowering period of available pollen sources to the insects at this time.

3.1.i Willow - Flower production

To observe the flowering dates of the local species of willow, the following procedure was adopted:

- Observation of flowering dates of willow.

- Observation of activities of honey bees at chosen Apiary.

- Species of willow were identified and regularly checked for flower production.

- Records were kept of the date of flower production and senescence of catkins.

- The length of flowering time was noted, between Feb 1 - April 1 and a table produced. Fig 4.1 See Chapter 4 for results

Fig 3.1 Salix caprea in full bloom January 28th 2005, Personal Photograph

Fig 3.2 Salix caprea Male catkins, Personal Photograph

3.2 The Bees Honey bees.

Following a visit to a Wirral Beekeepers meeting in January, and a discussion about this project; the implications for the beekeepers caught their interest. They are always concerned about the welfare of their bees, and what strategies might help the hives survive over winter.

Fig 3.3 The N.E. facing Apiary used for experimentation, Personal Photograph

It was possible to persuade a beekeeper to allow the writer to use his apiary.

The following records and sampling were proposed:

- Monitoring temperature and conditions in the Apiary.

- Monitoring the bees activities. (Results Table 4.2)

- Individual bees returning to hive with pollen were trapped.

- Pollen was removed from bee, and bee released.

- Labelled pollen sample was kept in freezer at -5°C.

- Pollen was mounted on a slide, and examined under a microscope to identify the source.

Table 4.2 See Chapter 4

3.2.i Activities of the bees

A table was constructed showing

The pollen source/s were noted, when possible from microscopic examination. It was hoped to compare the value of different plants to the bees at this time of year.

Fig 3.4 The hives, Equipment and Method of sampling, Personal Photograph

The Apiary was situated facing ENE; there were 7 W B C hives (Photo x) The intention was to observe the activities of Honeybees between February and April, and to sample the pollen loads of the bees as they returned to the hive. The apiary would be visited twice weekly at mid-day. The number of bees seen flying would be recorded and estimates of the % collecting pollen, noted. The pollen was to be stored and subsequently examined under the microscope for the flower source.

3.2. ii Sampling pollen loads.

- Trapping the bees and sampling of the pollen loads of bees entering the hive.

- Placing a pollen trap in the hive entrance.

Fig 3.5 Worker bee with load of Willow Pollen, Photograph (Hooper. T, 1979)

3.2. iii Choice of Method,

There appeared to be three options when sampling the pollen loads.

Methods of collecting pollen were considered

- Pollen to be taken from the bees while on the flower.

- Pollen to be taken from the bee returning to the hive.

- Inserting a pollen trap into the hive.

The advantages and disadvantages of each method of sampling bee pollen loads are shown in Fig 3.6

| Method | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Source of pollen is apparent, Search must be directed to the willow species | Difficult to catch the bees and remove the pollen No knowledge of available willow species at start of project. |

| 2 | It should be easier to catch bees on the alighting board and remove the pollen loads. Working with permission in an apiary in accessible conditions. | Do not know the source of the pollen before examination. No Knowledge of microscopy |

| 3 | Collection of a large sample possible | There were problems with the WBC type of hive in inserting a pollen trap It is unwise to open a hive in early spring, to remove the trap. The pollen collected could not be accurately dated. |

Method 2 was chosen for this investigation.

3.3. Equipment and Method

Equipment needed

Thermometer reading Centigrade

Small plastic beaker with holding handles

Piece of card to close beaker

Screw top jar

Stop watch

Labelled sample bottles

Small 0.5 cm paint brush

Refrigerator and freezer for storage.

Fig 3.7 Hand - made bee trap

A small plastic beaker was pierced with a red-hot wire, which was then bent to form a handle.

Fig 3.8 Bee with pollen in trap. Personal Photograph

Fig 3.9 Bee in trap prior to transfer for removal of pollen. Personal Photograph

3.3.i Pollen sampling

The bees were trapped as they approached the alighting board in a plastic cup, Fig 3.4 and the top covered by a card. The bee was then shaken into a sample jar with a screw top lid, which was put into a refrigerator at 5°C for 5-10 minutes to chill and calm the bees. It was possible to then gently remove the pollen from their legs with a dampened paintbrush. The pollen was then collected into a small sample jar, labelled with the time and date and placed into a freezer for storage. The bees were allowed to warm up and then released.

Fig 3.10 Graph to show the ratio of adult: brood in the colony showing the main period when pollen is required to build up the colony for the main foraging season Jun - Aug. (Hooper, Ted. 1979)

3.3.ii Suggested method for slide preparation (Archer M.2004)

De-greasing - (May not be necessary)

Pollen loads are decanted onto a clean watch glass, add a few drops Diethyl Ether. Short stir- drain the ether. Leave in a well ventilated place until ether has all evaporated completely.

Place de-greased pollen on a micro-slide with an insect-mounting pin.

Mounting the pollen use glycerine jelly mixture warmed to 40°C - (use bottle warmer)

Spread the pollen in a thin layer.

Place the micro-slide on a hotplate to allow pollen grains to absorb moisture and achieve maximum size.

One or two drops glycerine jelly are placed on to the pollen using a glass rod.

Put on a cover slip (preheated) Leave slide on the hotplate until the jelly distributes itself evenly under the cover slip.

After several days, seal around the coverslip with nail varnish. Store in cool dry place.

Hodges,D. (Undated) in the leaflet 'The Pollen Loads of the Honeybee' for The International Bee Research Association recommends (Maurizio, A. Undated) Method of swelling the pollen in either a little honey or glycerine. She suggests the use of Fuschin as a stain, because it has the advantage of being permanent.

Many of the writers on this subject stress the difficulties and the value of experience in slide preparation and reading. They are writing of pollen examination from the centrifuged honey, whereas this experiment was on frozen pollen grains.

CSIRO Atmospheric Research (2004) Australia) www.cmar.csiro.au

suggests a method using fuschin stain and glycerol. This seemed to be a simple method using readily available apparatus and stain.

3.3.iii Choice of Method and Slide Preparation.

The CSIRO method was chosen because of the simple description and available supplies. (See Appendix)

Caliberia's staining solution was used.

Preparation of the staining solution.

Materials

5ml glycerine 10ml 95% ethanol

15ml distilled water saturated aqueous basic fuschin

melted glycerine jelly.

The saturated aqueous fuschin was prepared in a McCarthy bottle.

5ml glycerol was melted in a beaker of water on a hotplate to around 60°C and added to 5mls basic fuschin.

In a 25 ml measuring cylinder, (before it cooled) were mixed: glycerine, ethanol, distilled water and the basic fuschin / glycerol solution. This is the Calberia's staining solution. It was stored in a clear bottle with a dropper lid. (all bottles were labelled with the appropriate chemical warnings following risk assessments under Health and Safety Rules)

Method of staining:

The exine of the pollen grains takes the stain, but fungus spores or other debris are not coloured.

A drop of Calberia's solutions was placed on the slide with a little pollen, using a wire loop. The mixture was gently stirred and covered with a cover slip.

After 10 minutes the pollen structure was observed under a microscope. The cover glass was sealed to the slide using clear nail polish.

Chapter 4 Results

4.1 Observations of the Flowering dates of Willows

Fig 4.1 Table of Flowering dates of Willow Species 2005

Compiled by Sylvia Briercliffe m = male species f = female species

| Species | Date flowers 2005 | Date of senescence | Duration | Native Species | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. caprea | m | Jan 28 | Feb 12 | 15 days | N | Great Sallow |

| S. fragilis | f m | Mar 28 Mar 30 | Apr 6 | 10 days | N | Crack Willow |

| S. cinerea | m | Mar 16 | Mar 31 | 16 days | N | Fen Sallow, Rain damaged pollen |

| S. alba | m | Apr 1 | N | White Willow | ||

| S. lanata | m | Feb 25 | N | Woolly Willow | ||

| S. chrysocoma | f | Mar 31 | Apr 16 | 17 days | Horticulture use | |

| S. sachalinensis 'Sekka' | m | Mar 4 | Mar 26 | 23 days | Horticulture use | |

| S. viminalis | m | Apr 6 | N | Common Osier | ||

Fig 4.2 Diagrammatic representation of Flowering dates of the Salix varieties.

This representation was drawn up from observations in Fig 4.1

Observations of local willows see Chapter 3.1

4.2 Observations of the Honey bees

Fig 4.3 Activities of honey bees between Feb 1 and April 1/04/05

| Month | Date | Time | Temp °C | Flying | Rate | Pollen | Approx % | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | 10 | / | 0 | |||||

| 29 | / | 0 | ||||||

| Feb | 2 | 1300 | / | |||||

| 3 | 1300 | / | 10-15 | 0 | ||||

| 10 | 1200 | / | 30-35 | / | 10% | Many coloured | ||

| 15 | 1300 | 5.56 | / | 10-15 | / | |||

| 16 | 1300 | 6.67 | / | 1-2 | 0 | |||

| 17 | 1300 | 3.33 | X | - | 0 | |||

| 20 | 1200 | 2.22 | X | 0 | ||||

| 21 | 1200 | 3.89 | X | 0 | ||||

| 27 | 1300 | 5.56 | X | 0 | ||||

| Mar | 3 | 1300 | 5.56 | X | 0 | |||

| 6 | 1300 | 3.33 | X | 0 | ||||

| 9 | 1300 | 7.78 | / | 40-50 | / | |||

| 13 | 1200 | 6.67 | / | 10-15 | / | |||

| 16### | 1200 | 13.33 | / | 60-70 | / | <1% | Oilseed rape flowering | |

| 17 | 1300 | 14.44 | / | >100 | / | <1% | ||

| 19 | 1200 | 13.33 | / | >100 | / | 5% | ||

| 23 | 1200 | 16.67 | / | 20 | / | 10% | ||

| 26 | 1500 | 13.33 | / | 60-70 | / | 5% | Rainy | |

| 31 | 1300 | 12.22 | / | 60-70 | / | 5% | ||

| Apr | 01 | 1300 | 13.33 | / | / | 30% |

### The bees were noted to be very agitated this day. It was discovered that a large field of oil seed rape was in flower, within a close distance from the Apiary. It is reported by beekeepers that this crop affects the collecting patterns of bees.

Fig 4:4 Bar Chart to show collecting patterns of honey bees in Spring

4.3 Observations of pollen collected.

Examination of slides of pollen collected

Reference slides

Willow... about 12 microns diameter

Oil seed Rape... about 25 microns diameter

See Appendix A & B Photomicrographs of Pollen Grains (Hodges)

Fig 4.5 Table to show the pollen examination results

| Date | Details | Size approx |

|---|---|---|

| Feb 10 | Very thick exine sculptured 3 pits Willow possibility | 12 microns |

| Feb 15 | Triangular shape, thinner exine, sculptured Hazel possibility | 20 microns |

| Mar 9 | Larger grains and smoother sculpturing Unknown source Possibly spring bulbs | 25 microns |

| Mar 16 | Grains very round with distinct small sculpturing Oil seed Rape | 25 microns |

| Mar 17 | Distinct small sculpturing, Oil seed Rape Brassicae family | 25 microns |

| Mar 19 | Definition not picked up. These were large pollen grains, Unknown source | 40 microns |

| Mar 23 | Central area defined in the sculpturing Contamination among the grains, Unknown source | 20 microns |

| Mar 26 | Debris. No obvious pollen grains | ---- |

| Apr 1 | Triangular shape, Took stain heavily, Very dark sculpturing, Unknown source | 20 microns |

Appendix C shows Laboratory Notes taken at time of observations.

Explanation of content of slides.

Method of approximately sizing the pollen grains.

When viewed the slides of pollen examined contained some variety of grains.

These under the microscope required an expert eye to identify.

As there was no method of measuring the pollen size on the microscope available, this was estimated by comparison with the width of the microscope field, and checked against the known size of the two Reference Slides made of the Oil seed Rape and Willow pollens.

Chapter 5 Discussion

5.1 The flowering dates of willow

The study of willow is confusing; many writers state that hybridisation makes identification difficult (Newsholme. C 1992 & Mitchell A 1972) With 19 native varieties; there is wide distribution in most locations. Recording of specific varieties requires experience and practice, which the writer did not have at the beginning of the project.

The proposal was to begin recording and pollen collection at the beginning of February when literary sources stated that willow varieties would start to produce catkins and to continue until the end of March when the bees would have other sources of spring flowers to harvest.

However this year (2005) it was discovered that mature goat willow trees started to flower, probably around January 20th, and were well into blossom by January 28th and the table produced in this study (see Fig 4.1) did not match that in (Fig 2.5) from the Web site of 'Science and Plants for schools' this year. However Table (Fig 4.2 ) shows that there was a succession of willow varieties in flower from January 20th until well after the recording stopped on April 1. At the time of writing S. alba is still in bloom. (May 10th 2005)

The writer was both inexperienced in the identification of willow varieties and the local distribution of willow trees and bushes, studying the literature shows confusion between very experienced botanists. Mitchell, A tells us that Salix x chrysocoma (the Golden Weeping Willow) Is "normally only a male clone,(with occasional female flowers)" whereas Newsholme C. says it is of "indecisive sex - both male and female on same, separate branchlets, and with bisexual flowers". The weeping willow tree in the garden at the apiary, the writer thought was totally female. The bees were able to gather nectar, if not pollen.

All writers agree that willow are entomophilous, -pollinated by insects- The National Pollen and Aerobiological Research Unit finds that Hay Fever sufferers are not usually affected by the pollen. McGavin,G.C. (2001) comments that using bees and wasps as "flying genitalia" confirms the opinion that insect pollinated plants are an evolution from wind pollinated ones, and people with allergies would agree!

Observations during this study have demonstrated the attractiveness of all Willow for a large variety of flying insects. There have been many such insects visiting all the willow plants

5.2 Short Rotation Cropping

Redderson (2004) in his studies on Short Crop Rotation Plants of Salix viminalis concluded that a plantation with both male and female cutting material, would provide a more diverse biotope, when flowering because it produced both nectar and pollen. This was because females give only nectar, but male plants give both nectar and pollen. He also noted that planting a variety of willow clones, would give an extended flowering season, which this study confirms. A third suggestion was for the plantations to limit the herbicide and to allow wild plants to flourish; especially in the grass 'rides' between the plots.

Redderson's research was hindered by a lack of bees local to the plantations. The writer feels that male- only clones could be a more fruitful source of pollen and nectar than planting males together with females.

This study conducted in the north of England and Wales found that S. viminalis flowered in April, at the end of the period that was crucial to the brood building time. The traditional coppicing harvest seemed to be of the Common Osier in Britain, but perhaps early flowering willows e.g. S caprea could prove a more ecologically friendly crop for biomass, with the addition of good foraging for both honey bees and other insects at this brood rearing period.

It is an exciting possibility that biomass fuel production using suitable varieties of willow may have a beneficial effect to ecology, by providing a rich habitat where nothing existed before.

Nottingham University has also experimented with phyto-extraction of sewage sludge using SRC willow to remove heavy metal contamination. (Web Site Nottingham University)

5.3 Activities of the bees.

The proposal was to start recording at the beginning of February and continue until the end of March; which is considered the period at which the queen bee is stimulated to lay. New fresh pollen is thought to contain the pheromones that stimulate laying. The brood takes at least five weeks before the young bees are ready to begin pollen and nectar collection in the main honey flow in May and June, which means that pollen must stimulate laying at least by the end of March. It needs to start even earlier for bees to benefit from the flow with oil seed rape.

The bees were finding pollen to collect by February 10th and were collecting yellow and orange colours. The apiary was situated where they had access to a rich source of spring flowers, from trees, bulbs and herbaceous plants, most of which were flowering by Mid March. This could have diminished the amount of willow pollen that they needed to collect, especially as the flowers were adjacent to the hives. In early spring the bees are flying in difficult, cool conditions, they do not have the stores of nectar to provide them with energy to fly very long distances.

Recording the temperature in the apiary was not started until Feb 15th, which was a failure in planning the experiment. It would also have been beneficial to note which days were sunny, although facing N.N.E. the hives were not exposed to the sunshine until late afternoon.

It can be seen that apart from one exception (Feb 15th,) the bees did not fly if the temperature was under 6°C. This is confirmation of documentation. During the period of pollen sampling, there was one occasion that the bees were very agitated (March 16th) It was impossible to sample that day, but no pollen was observed being brought into the hive. A large field of Oil Seed Rape (Brassicae, family of plant) was coming into flower. The writer, when keeping bees had experience of aggression from the bees when collecting from this crop. The bees are diverted from all other sources of nectar

5.4 Pollen collection.

On microscopic examination the writer was not sure that there had been Salix pollen collected. The grains collected on Feb 10th were of a similar correct size, and shape, and certainly there were many insects visiting all the willows as they flowered.

The grains from March 16 and 17 were the size and had similar sculpturing as the drawing of the cruciferae/ brassicae family plants drawn by Dorothy Hodges. In her book 'The Pollen Loads of the Honey Bee'. With time restraints there was no chance to get an expert opinion. And the College did not have anyone experienced in palynology.

5.5 Future work and improvements to the experimentation.

The recording could be greatly improved by a more experienced practitioner, with knowledge of both the varieties and the distribution of Native Willows.

An experiment to test more scientifically for the range of pollen being collected by the bees between February and April could be devised. It would need to be much more sophisticated with specialised equipment. Pollen traps can be inserted and removed without chilling the bees if National Hives were being used. This would give a more frequent and much larger sample of the pollens being brought in.

It can be fruitful to observe the bees as they forage for pollen in the spring. Entomologists have methods for trapping insects on the plants to release the pollen to confirm the usefulness of Salix as a source of pollen. Bee keeping is often considered an art rather than a science. It is often said that there is a relationship between the beekeepers and their bees.

The writer experience, the method used by experienced beekeepers to judge the source of their honey (and thus the pollen source) is by matching the colour against a colour chart such as that prepared by artist/ beekeeper/ writer Dorothy Hodges.

Personal Photograph of the field of Oil Seed Rape.

There is no doubt that Oil Seed Rape provides excellent foraging for honey bees and other insects, if the farmer is not using pesticides and herbicides.

However it cannot provide a diverse habitat. It would be an interesting comparison to this project to be able to choose an apiary in a more rural setting with known lack of other pollen sources at this time.

It will always be beneficial for beekeepers to have native willows, within a short distance, early in the year. It is amazing that John Evelyn recognised this fact 400 years ago.

References

Ailner, J. Edward (1992) 'The Tree Book' Collins and Brown Ltd

Applin, (1994) Key Science Biology, p.20 In Chigwell School Site 'Energy Pyramids' www.chigwell-school.org accessed 20.4 05

Begon, M, Harper, J.L,, Townsend C.R, 'Ecology' Blackwell Scientific Publications Oxford

CSIRO [www document] 'Atmospheric Research' www.dar.csiro.au/airwatch accessed 4.5. 2005

Culpepper (1826) 'Complete Herbal & English Physician' J. Gleave & Son Manchester.

Dictionary of Botany (1984 ) Ed Tootil. E, Penguin Reference Science. England

Elton Charles Sutherland, 'Concept of food chains.' (2005) [ www Document ]. Accessed 20.11.04

Emberline. J.C., 1983. 'Introduction to Ecology' Plymouth: MacDonald and Evans Ltd

Evelyn, J. (1664) 'Silva, A Disclosure of Forest Trees and The Management Of Woodland' Keynes [ www Document ]. Accessed 20.10 2004

Haeckel (1834 - 1919 Biography ) [www.document ]. accessed 20.11 04

Heywood., V.H. (Ed,) (1998) Flowering plants of the World Batsford London

Hodges, D (1952) 'The Pollen Loads of the Honey bee' International Bee Research Association London

Hooper, Ted. (1979) Guide to Bees and Honey Blandford Press, Poole.

Jens Reddersen Science Direct 'willow (Salix viminalis) as a resource for flower-visiting insects' Biomass and Bioenergy, Vol20, Issue 3 March 2001

McGavin. George, C (2003) 'Essential Entomology' Oxford University Press Oxford

Mitchell. A., (1978) 'A Field Guide to the trees of Britain and Northern Europe' Collins, Glasgow.

Newsholme, C., 1992 'Willows' London: Batsford

Nottingham University [www document ]. Accessed 10.5.05.

Rowland-Entwistle, T (1976) 'The World You Never See -Insect Life' Hamlyn London

Strong, D.R. J.H. Lawton, Sir Richard Southwood (1984) 'Insects on Plants (Community patterns and Mechanisms' Oxford Blackwell Scientific Pub

Teachers Work Sheets [www document ]. Accessed on 26.04.05

The British Beekeeping Association [ www document ]. Accessed 10.02.05

CIRIA Contaminated Land [www document] www.contaminated-land.org

Zahradnik, J. (1998) 'Bees and Wasps' Blitz Editions, Leicester

Written... 11 to 31 August 2005,

|