For demonstration purposes and for my own queen rearing I use most of the standard methods of producing artificial queen cells. In my experience, they all work well and I'm happy to use any of them. I have used the cell punching method since the late 1960s and it is still my favourite method. An old beekeeper had a set of "Stanley" cell punches that were sold by Badgerdell Apiaries (see "History of Cell Punching" below). He had never used them, so he gave them to me. I often see beekeepers who have had unused cell punches for years. Very often they don't know what they are or how to use them.

I am the only person I know who uses cell punching on a regular basis, which I think is a pity, because it is such a simple method. Cell punching is much discredited and ridiculed, mainly by those who know nothing about it and have probably never used it, which only puts others off using it. Cell punching in various forms has been used for many years, but has never been popular, probably for the usual reasons why things aren't popular in beekeeping - there is specialist equipment needed that has a cost to it and those in influential positions don't know anything about it, so they rubbish it. Sorry to be so cynical, but I hope I can encourage beekeepers to use a system that has a lot of merits.

There are holes punched in brood combs and this is seen as a disadvantage by some. It is true that bees don't usually fill in the holes, but I believe they use them as passageways around the brood nest, as they are roughly the size of a beespace, so they probably do a colony some good.

The cell punch method is simple and you have no need to handle the larvae, as you have to with some other methods, such as grafting. All we are doing is punching out a cell with a worker larvae of the right age from an existing brood comb. It could have been the larva that you might have grafted. It's that simple!

When I give lectures and demonstrations there is often much more interest in cell punching than all other methods, but I suspect many don't pursue it. It may appear easy to make the cell punches, but a little thought needs to be given to it.

Although at the time of writing the parts aren't commercially available, they are quite easily made from readily available parts. If you are making the punches, I must comment on the drawing below that was made by Dave Cushman. Dave copied one of my punches that was commercially made, but I think they can be improved slightly.

A common suggestion is to use small bore copper pipe for the tube, but this is too soft. It needs to be quite hard, such as brass or stainless steel, to maintain a reasonably sharp cutting edge. The internal diameter is 8mm, but slightly larger will do. This can be from any source, but spent bullet cases are also suitable, so if you know someone who goes shooting you may get some from them. I believe the only purpose of the plastic nose is to hold the punched cell in place so it doesn't drop out. The hole through it therefore needs to be 0.5-1mm smaller than the metal tube, which is different than the drawing. I have never tried it, but I guess the end of the tube can be squashed in a bit to do the same job. This is already a feature of a bullet case where the end is swaged in. The wooden dowel can be bought cheaply from a DIY shop and glued into a larger piece to create the stepped dowel as indicated in the image below. The tip of the wooden dowel when assembled in the punch should be 5mm back from the front of the plastic end. The operation works better if the dowel is a good slide fit in the tube, not a sloppy fit.

The benefits of cell punching are:-

- You select the larvae of the correct age.

- You don't touch the larvae, so they are unlikely to be damaged.

- Rejects can be re-punched or grafted into the punched cell the bees have removed the larva from.

- You can take larvae from one or more colonies to fit in the same cell bar.

- You can rear a small number of Q/Cs, but as many as you have cell punches for.

- Suits all beekeepers.

The image at right shows a complete cell punch with plastic nose and the wooden dowel.

My method of use.

On a brood comb that is taken from the colony you wish to rear queens from, select a cell that contains a suitable larva. Make sure it is not over a frame wire, otherwise you may blunt the cell punch. Put the sharpened end of the cell punch over the cell so the tube encircles it, as shown at far right.

Push the cutting edge right through the comb with a twisting or turning motion as shown above left, then withdraw it with the punched cell inside. Punching is easier if the comb is laid on a piece of plywood or board, so you can cut against it.

Young comb will easily collapse, making punching difficult. Old comb will have a lot of cocoons in it, so will be tougher to cut. There is a happy medium and with a little experience you will know what works the best for you.

The punched cell looks like the image at far right below, the cell itself is inside the tube. In the right hand image what you can see protruding is the fragments of cells from the reverse side of the comb.

Using the dowel as a plunger, the contents of the tube are pushed through fully, so the cell is exposed slightly beyond the mouth of the plastic collar.

The selected cell is shown on the right protruding from the mouth of the cell punch.

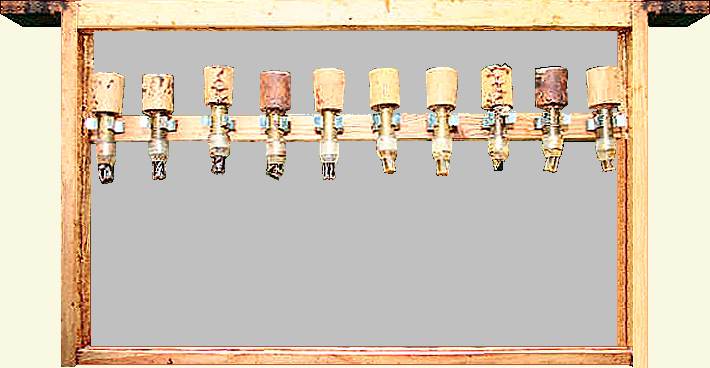

The dowel is a slide fit on the tube, so if you hold the cell by the dowel the tube will fall off in the cell building colony. To prevent this happening I use a brood frame with 10 "Terry" clips fixed to a wooden bar, so the clip grips the tube, not the dowel.

The 'Terry' tool clip is shown at right. They are used for holding things such as round tools and are available from DIY or hardware stores in various sizes. They should be selected to give a reasonable grip to the brass tube of the punch, so they can be clipped in and removed easily.

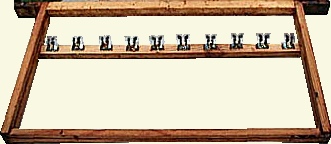

The frame is prepared with a wooden bar fixed to the side bars, about 2ins/50mm from the top bar, to accept the row of 'Terry' tool clips. The frame is shown empty for clarity on the right.

If larger frames than the British Standard are used, then use as many clips as you wish. One row of 10 clips suits me and my bees. I tried a frame with 2 rows of clips, but my bees wouldn't accept more than about 12-15 larvae. More prolific and more swarmy bees probably will. If you put two rows, you don't have to use them all.

A frame filled with cell punches will look like the image below. The grey background has been included to show the punches more easily. Do not be too concerned about the cleanliness of the punches, the bees seem to use them if simply cleaned by hand, often accepting them better than fresh or 'cleaned up' ones.

If you leave the punched cells "as punched" like those shown in the image above, the bees will have to chew the sidewall of the cell away. To save them having to do this work, I either cut it back with a sharp knife or scalpel, or slice through the cell lengthways, folding back the sidewalls and pressing against the plastic collar.

The bees will start to work on the cells when the frame is inserted in the cell building colony. After a

little time has elapsed the cells will be seen to be fully provisioned with royal jelly as the one at near right shows.

I usually check initial acceptance after a couple of hours, if not, then after about 24hours, when the cells will look like the image at far right. Any larvae that have not been accepted

can be re-punched or grafted. If done 24 hours later, then make note as they will emerge about 24 hours later than the others in the bar.

The objective in all of these operations is to produce sealed queen cells that

look like the excellent example at far right.

The sealed cells can be placed in a nucleus or colony for emergence in the same way as you would any other cells. The large diameter wooden plugs can be removed, or simply pressed into the face of the comb or in an existing hole or gap to secure the cell sufficiently to prevent it dropping (the bees will soon fix it). In a colony that is densely populated with bees, I like to place the Q/Cs in the gap that bees often leave between the comb and the side bar of the frame.

The image, near right, indicates what the cell looks like after the virgin queen has emerged.

If the receiving colony hasn't been queenless for long, the cell may need to be protected. There are some ways of achieving this on the cell protectors page. There is no obvious way of protecting punched cells, but a simple way is to wrap aluminium foil around the whole assembly as shown on the right.

History of Cell Punching.

Cell punching is mentioned in L.E. Snelgrove's book "Queen Rearing", where he writes of an article in "Journal d'Agriculture" of Quebec published in March 1918, which details a method by E Barbeau. Mr E Barbeau, of St Eustache, Quebec had an article published in the July 1919 edition of the American Bee Journal (ABJ). This was reported in "The Bee World", August 1919 edition as "The Barbeau System of Queen Rearing". There was an addition in the Sept 1919 edition of ABJ to complete the July article. The January 1920 edition of ABJ stating that Mr Barbeau ".......is the only man selling the implements of the Barbeau system". I have been unable to find out if Mr Barbeau was an equipment supplier or just sold his cell punches. The December 1919 issue of "The Bee World" carries an article where Mr Barbeau describes three methods of rearing queens using his system.

I have not seen some of the accounts mentioned above, but from what little I have gleaned, it seems possible that Mr Barbeau was developing a system that resulted in the cell punching method as we know it today. Certainly there were some features in the early accounts that were not mentioned later.

Apart from the 1920 edition of the book "Dadant System of Beekeeping", where the author C.P Dadant mentions ".......the still more modern Barbeau method....." and Snelgrove, I have found virtually nothing until the 1940's, when a very similar system was promoted by P.W. Stanley FRES of Badgerdell Apiaries, Kings Langley, Hertfordshire. These were the "Stanley Cell Punches" that I was given in the late 1960's. I know little of Badgerdell Apiaries, but at one stage they apparently made and sold a complete system that included relevant parts. They also made and supplied other equipment, including artificial insemination equipment. I don't know how long they were operational, but probably not for very long. I have seen a later advertisement from them with an address in Chichester, West Sussex. They presented the "Badgerdell Cup" to the National Honey Show in 1950. Mr Stanley wrote an 8 page booklet "The Stanley System of Queen Rearing". Following an appeal in the bee press to locate a copy, the Scottish Beekeepers Association Library Officer, Una Robertson, kindly sent me a photocopy of one held in the Moir Library. The original appears to have been hand typed and duplicated. There is no publication date or price, suggesting it may have been supplied with equipment. The contents are without photographs or drawings, making it difficult for someone without the cell punches to follow the brief instructions. Bearing in mind the closeness to the method of Barbeau, it is reasonable to assume that Stanley may have copied and was credited for the invention of Barbeau.

In 1970 BIBBA published an excellent booklet "Raise your own queens by the punched cell method" by Richard Smailes. The second edition was dated 1977, but it is now out of print. I was asked by BIBBA to update this, but ai felt there was much to add and I felt it was disrespectful to Mr Smailes, who I never knew. I decided to write a new book that is titled "Queen Rearing Made Easy: The Punched Cell Method".

The last commercial suppliers of cell punches were Steele and Brodie (1983) Ltd, who were dissolved around 1970. I have a single page instruction leaflet they included with the cell punches, where they state that sets of 5 or 10 cell punches includes the Smailes booklet. This suggests to me that perhaps BIBBA encouraged Steele and Brodie to stock the item.

I have seen a number of attempts at cell punching, but none have come close to this method. Most alternatives are much more complicated and probably unlikely to be used widely by others. A selection can be seen by pressing the "Cell Punch Alternatives" button at top left

If you are aware of any further information on cell punching, Barbeau or Stanley please Email me.

Conclusion.

I think the cell punching method is an excellent method of rearing queens. For over half a century I have raised thousands of queens by this method and I have enjoyed doing it, as I always do when seeing a good home raised queen. I hope this page and the above mentioned book will encourage others to consider using it.

I think there are several reasons why the punched cell method has never been popular. There has never been a regular supply of good quality cell punches and apart from the booklet by Richard Smailes, there is little information on their use. I hope to put that right by reorganising this facility and the publication of the book.

The original photos used on this page were provided by me and manipulated for this page by Dave Cushman.

Originally written by Dave Cushman. Edited and additions by Roger Patterson.

Page created pre-2011

Page updated 18/12/2022